Japanification of Europe

Summary

- Macroeconomic indicators show that the”Japanification” of the Euro area is currently taking place.

- We expect the Euro area inflation to stay at current levels for the next couple of years and therefore, also the super low-interest-rate environment to remain unchanged.

- Although low-interest rates, weak inflation and declining growth all point to a European Japanification, there are several limitations when comparing Japan with the Euro area.

- Therefore, we argue that Japanification is here to stay, albeit for different reasons than in Japan.

In recent years there have been several discussions about whether Europe is going to be the next Japan due to the weak economic conditions that it has faced in the last ten years. At the end of 2018 when ECB President Mario Draghi hinted that most probably there would be no interest rate hikes in 2019 either, it suddenly became clear that the Euro area was indeed on the path of “Japanification”.

When it comes to the phenomenon Japanification we define the term as a series of unconventional measures, such as quantitative easing, different bond-buying programmes and a constant low- interest-rate environment in order to boost inflation and restore the economy to normal conditions. In this report, we are going to present first the history of Japan and how it became one of the most powerful economies after the Second World War. Afterwards, we discuss the crisis that was triggered by the Japanese asset price bubble in 1990, following the 1997 Asian crisis and ultimately the recent financial and economic crisis. In the third part, we outline the reactions of the two central banks and their measure to fight recession. Finally, we conclude that Japanification is indeed happening in the Euro area but for different reasons than in Japan.

History and Background: Japan between 1945 and 1990

After the Second World War drastic reforms were introduced in order to make Japan a powerful global economy. Mirroring the USA’s “New Deal” of the 1930s, Japan’s traditional family-owned monopoly order was broken up and the new system introduced liberalization and deconcentration of industries, aiming to build a state-model geared towards economic growth. By combining traditional Japanese concepts and values with liberal, free-market oriented policies originating from the US, as a result, new types of conglomerates emerged from the old Japanese system which led to the period now referred to as the “Economic Miracle”.

Beginning from 1947 policymakers started steering the newly emerged companies into promising industries, such as automotive manufacturing and later consumer electronics. These were heavily promoted internationally in a state-led plan to boost exports while at the same time reducing imports, which led to a large trade surplus. The most prominent examples of high-quality Japanese exports are cars and motorcycles, which were sold to the US en masse during the 1970s by firms such as Toyota and Honda.

By 1955 the Japanese economy had already grown beyond pre-war levels. The next two decades brought unprecedented economic growth and social welfare. As a state that put all forces into growing its economy, by all means, Japan profited heavily from employees bound to single corporations. The lifetime workforce became its number one distinguishing asset from other industrial economies, and even today it is known for its workers unique discipline, loyalty and willingness to work extreme hours. These factors led to extreme success: during its peak in 1987 the Nikkei had become the largest stock market index by market capitalization and Japanese GDP per capita had reached an all- time high of nearly USD 25,000 in 1988, which is a 5,120% plus compared to its value of USD 479 in 1960.

„By combining traditional Japanese concepts and values with liberal, free- market oriented policies originating from the US, as a result, new types of conglomerates emerged from the old Japanese system which led to the period now referred to as the “Economic Miracle.”

Economic success did not last forever since a good part of the economy was built on an unhealthy ground. In the Plaza Agreement of 1985, the USD was depreciated against the Yen in an effort led by the FED to stabilize global exchange rates. After signing the deal, BOJ continued providing loans aggressively and neglected poor credit ratings in order to further boost its economy with the goal of becoming the world’s number one economy in the foreseeable future. The subsequent overheating effect steadily led to an asset price bubble of tremendous size. Between 1985 and 1989 alone, the Nikkei index grew from USD 12,000 to an incredible USD 38,957 on the last trading day of 1989 – a plus of 224% in not even five years.

„The lifetime workforce became its number one distinguishing asset from other industrial economies, and even today it is known for its workers unique discipline, loyalty and willingness to work extreme hours.”

The Japanese crisis

After 40 years of economic prosperity and unparalleled growth, Japan ran into the worst crisis since World War II. After the trade surplus fell from 13.9% of GDP to 9.6% of GDP due to the Plaza Agreement, the BOJ cut interest rates from 5% to 2.5% between January 1986 and February 1987 and dictated massive loan quotas upon the banks. This caused a massive bubble, asset prices rising in the six biggest cities by an unbelievable 302.9% between 1985 and 1991 and – as mentioned above – the Nikkei by 224% between 1985 and 1989.

“This caused a massive bubble, asset prices rising in the six biggest cities by an unbelievable 302.9% between 1985 and 1991 and the Nikkei 224% between 1985 and 1989.”

“… the Nikkei lost 23% of its value in the first quarter of 1990 and 60% of its value until summer 1993. Similarly, real estate prices in Japan’s six biggest cities plunged by 20% in 1992.”

As a result of the growing asset bubble and inflation, the BOJ started hiking interest rates from 2.5% in May 1989 to 6% in August 1990. This sharp reversal of policy caused a crash in the Japanese stock market. Compared to the last trading day in 1989, the Nikkei lost 23% of its value in the first quarter of 1990 and 60% of its value until summer 1993. Similarly, real estate prices in Japan’s six biggest cities plunged by 20% in 1992. The crisis forced a lot of banks and other companies into bankruptcy and left banks full of bad debt – in 1997 the Japanese ministry of finance estimated bad debt at 12% of all loans. Since the crisis hit, Japan continuously experienced low inflation or even deflation, low growth and rising debt. Japanese government debt reached 253% of GDP in 2017, which is by far the highest government debt of any country.

Just like the Japanese crisis, the financial crisis of 2008 was triggered by a bubble. The subprime mortgage market in the US crashed, American banks being heavily affected and then the whole world experienced a domino effect. One of the main reasons of the crisis was the easy accessibility of loans during the 2000s that encouraged high-risk lending and borrowing practices very similar to Japan.

In Europe, after the introduction of the Euro the ECB slashed the average interest rates in Southern European economies because the ECB and the financial markets increasingly saw the Euro area as one country. For example, Spain’s average interest rate went from 10% before the Euro to under 5% after its introduction. This fuelled a real estate and debt bubble similar to the one in Japan.

Another reason for the European crisis was the negative trade balances in the Southern countries. Due to the relative strength of the likes of Germany, the Euro had simply been valued too high for the weak Southern countries which caused them to lose their competitive capability. To react to the slowdown, Southern economies increased their government spending which caused their debt to skyrocket. This caused a huge loss of confidence, making it more expensive for these countries to obtain new debt, eventually forcing the other Euro area countries to bail out five countries in 2009.

Central Bank Policies – BOJ and ECB

In 1989 the BOJ decided to cool down the economy by hiking interest rates from 2.5% to 4.25% throughout the year. When the crisis kicked in early 1990, the BOJ further raised interest rates to 6%. Only in 1991 – 17 months later – did they finally start gradually lowering interest rates again, to 0.5% until the mid-1990s and then to 0% in 1999. Regardless, Japan slipped into deflation in 1998. Because low inflation could not be stopped using conventional measures, the BOJ introduced quantitative easing in 2001 and the Japanese government acted as a guarantee for banks and financial institutions. However, even with these measures Japan’s property prices today are still at only 40% of their values before 1990 and the Nikkei never reached its peak from before the crisis again.

During the 2008 crisis, major central banks reacted in a similar fashion. Like other central banks, the BOJ’s first reaction to the crisis of 2008 was to lower interest rates. To calm the stock market the BOJ suspended the sale of their stocks but resumed purchasing stocks from financial institutions. This temporary measure was ended again in April 2010. Furthermore, the BOJ made outright purchases of Japanese government bonds. Later, those outright purchases were extended to commercial papers and corporate bonds. Additionally, the BOJ provided loans to financial institutions totalling one trillion Yen.

The ECB’s main aim is to ensure price stability, which is defined as an inflation rate of 2% per year. In contrast to the BOJ, the ECB takes actions not just for one country, but for a heterogeneous region. As its first reaction to the crisis, the ECB – similar to the FED and the Bank of England – lowered interest rates in 2008. This cut from 4% to 1% marks the largest interest rate cut in the ECB’s history. Ever since then, the interest rates have been kept low.

In addition to that, the ECB provided liquidity to the banks by implementing a new fixed-rate allotment tender and by taking on more assets as collateral, thus preventing a breakdown in the interbank market. As a reaction to deflation in 2015, the ECB introduced quantitative easing, purchasing bonds issued in the Euro area worth a total of EUR 60 billion on a monthly basis. Furthermore, the highly criticized Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program consisted of the ECB buying government bonds from the secondary market. This program was never enforced to the planned extent.

Inflation and interest rates

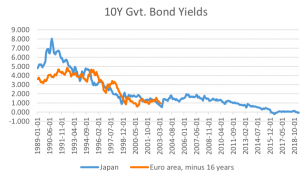

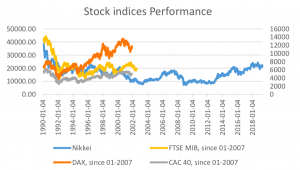

To answer the question of whether there is Japanification happening in the Euro area, one first has to define Japanification. Under this terminology we understand a permanent low-interest rate environment as well as a slumping economy, by which we mean low inflation, low GDP growth and a high debt-to-GDP ratio. Due to the low interest rates, the central bank is very limited in its capabilities to stimulate GDP growth and inflation back to a healthy level. As can be seen in Figure 2 and in Figure 3, interest rates and GDP growth are approximately on the same level (note that the Euro area data is minus 16 years). Similarly, Euro area inflation has been hovering around 0% for years, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 5: Japanification completed

Figure 6: Northern versus Southern European stock indices

ConclusioTo sum it all up, there are three major conclusions to be drawn. Firstly, the respective crises of Japan and the Euro area had different catalysts and a build-up that are not one to one comparable. Secondly, these crises led to a similar environment of low interest rates, low GDP growth and low inflation, which we define as Japanification. Thirdly, Japanification is here to stay, albeit for different reasons than in Japan.

The main issue in the Euro area is the stark contrast between the northern and the southern countries. As mentioned above, the introduction of the Euro as a common currency took the instruments of monetary policy away from the various central banks of the Euro area. Because of this, the ECB received the incredible duty to create and manage one suitable monetary policy for 19 different countries. Determining a monetary policy that fits e.g. both Germany and Greece caused and will cause further headaches for policy makers.

Because of this structural problem, the ECB will not be able to hike interest rates in 2019 and possibly in the years to come. Southern economies are still far too weak to endure higher interest rates. In order to overcome this substantial competitive difference, southern economies will need to keep lowering their real wages and government spending relative to northern countries, so that the competitive difference diminishes. Since southern countries are already on the brink economically as well as socially, this process will take a long time.

Disclosure The authors and editors involved in the preparation of this market research report hereby affirm that there exists no conflict of interest that can bias the given content.

Ownership and material conflicts of interest The authors, or members of their respective household, of this report do not hold a financial interest in the securities and/or positions mentioned. The authors, or members of their respective household, of this report do not know of the existence of any conflicts of interest that might bias the content or publication of this report.

Receipt of compensation The authors of this report did not and will not receive any monetary or non-monetary compensation from this report; neither from individuals nor from corporate entities.

Position as an officer or director The authors, or members of their respective household, do not serve as an officer, director or advisory board member of any possible subject company aforementioned.

Market making The authors do not act as a market maker in the aforementioned securities. Furthermore, the information nor any opinion expressed herein constitutes an offer or an invitation to make an offer, to buy or sell any securities, or any options, futures nor other derivatives related to such securities.

Disclaimer The information set forth herein has been obtained or derived from sources generally available to the public and believed by the authors to be reliable, but the authors do not make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy or completeness. The information is not intended to be used as the basis of any investment decisions by any person or entity. This information does not constitute investment advice, nor is it an offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security. This report should not be considered to be a recommendation by any individual affiliated with WUTIS – Trading and Investment Society.