The Indian Rupee in freefall?

Comprehensive Analysis

Summary

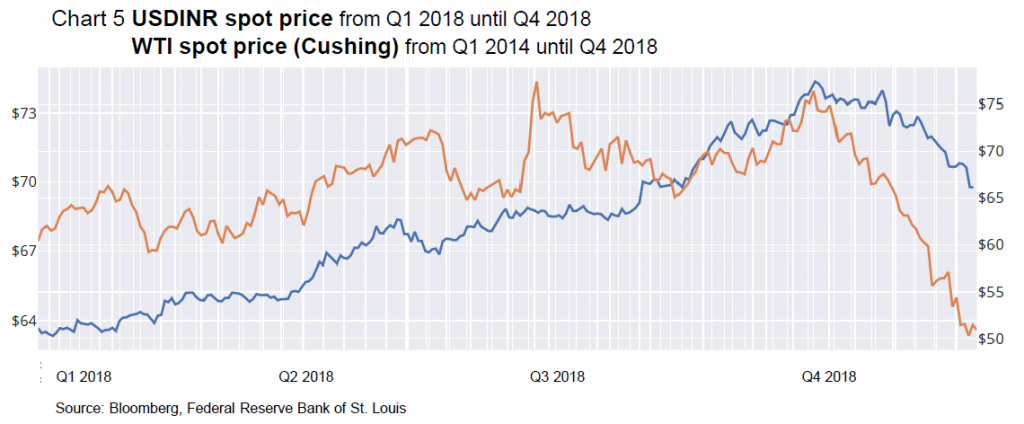

- A reverse in oil prices will severely hit INR until Q1 2019 after its further retrace to levels around 65.5 to 69

- INR has appreciated more than 6% in the last 8 weeks supported by the price drop of WTI Crude to levels below $50 since Q4 2018

- The long-term outlook is still driven by India’s current account deficit, the increasing demand for oil, although we expect a less rapid depreciation compared to the beginning of the year

At the beginning of 2018 financial institutions turned their attention to emerging market assets with great hope of generating attractive returns and diversifying their portfolios. Since then we have seen two corrections this year and generally, when it comes to emerging markets, market sentiment is not as positive as it used to be. The aim of this research report is to examine one of the largest and most significant economies, India in order to gain insight into the characteristics of emerging markets currencies and their role within the financial markets. The report focuses on the recent movements of the Indian Rupee and its dependency on the US Dollar, the commodity market, and oil.

Although the government has been diligent in its development of the country, there are still limitations to the growth of India. Uncertainty about India’s commitment to economic reforms, retrospective taxes, and policy paralysis within the government have forced investors to generally stay an arm’s length away from a broad investment in India.

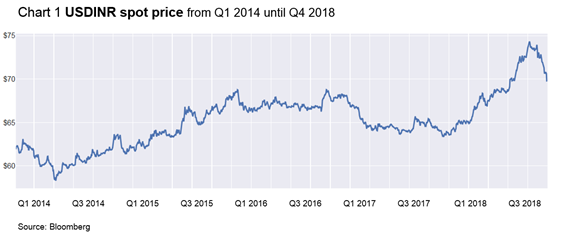

After the Modi government got elected in 2014, INR started to steadily lose value falling more than 13% to levels between 65.5 and 68.5 until late 2016. During the last year, it saw a minor rebound ending at around 63.2 in January 2018.

Since then INR has experienced a drastic decline, becoming one of the worst performing emerging markets currencies in 2018. Only the abrupt increase in oil output has reversed the currency’s trend, bringing it currently up to around 68.7.

RBI’s efforts in inflation stabilization

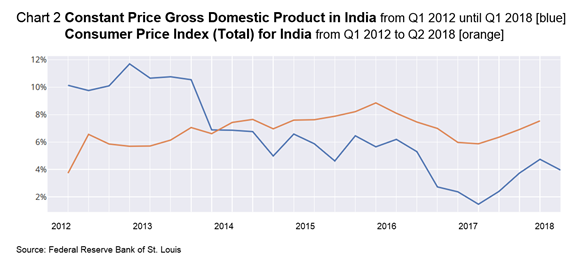

The question which arises with such a regime is, whether this is a suitable approach for a country that is partly facing supply constraints, especially, since food and beverages make up 45.86% of the combined CPI. In the post-crisis period until the end of 2013 India experienced an inflation rate of around 9%. Since 2014 the rate has lowered to below 4%. The inflation target until Q1 2021 is 4%, with an upper and lower band of 6% and 2%, respectively.

Additionally, the RBI is withdrawing excess liquidity through governmental security sales through their market stabilization schemes. They were first introduced to reduce liquidity generated through RBI’s purchases of foreign emerging markets currencies. Since 2002 there has been massive foreign capital inflow which led to an appreciation of the Indian Rupee. The result was a negative effect on exports. Because of that, the RBI started to buy US Dollars with Rupees, which in return led to higher liquidity and thus higher inflation. To outbalance higher inflation the RBI started to reduce liquidity by selling government bonds – a process called sterilization.

Nonetheless, the application of monetary policy and its transmission is weak since the RBI is the main money supplier of banks. Interest rate cuts will only affect new capital but not existing deposits. Moreover, banks do not favor lower the rates, as otherwise, their margins go down as well.

Finally, since India’s bond market and financial markets are still not well developed, corporate borrowers are still largely dependent on banks to receive funds. In order to improve this situation, the Indian government and the RBI have planned to take steps to accelerate the monetary transmission. The government wants to reduce interest rates on small savings accounts. If this rate is correlated to bank rates this might be a long-term solution.

In addition, the RBI wants banks to redo their calculations of the base rate to the marginal cost of funds from the previous average cost of funds. Even though banks have increased their lending rate after RBI’s rate cuts, the RBI cannot control inflation rates, due to a financial deficit, supply-side shocks, highly volatile oil prices, and agricultural issues. The financial conclusion is missing, as there are still lenders that are not under RBI’s control. Moreover, there are still parts of rural India that are not fully monetized. So far, the RBI has followed a neutral stance, as inflation has been at around target at 4% with GDP growth at 2% per quarter since Q2 2017. Therefore, it is not expected that the RBI will try to infuse or remove too much money into and from the markets.

Debt & USD

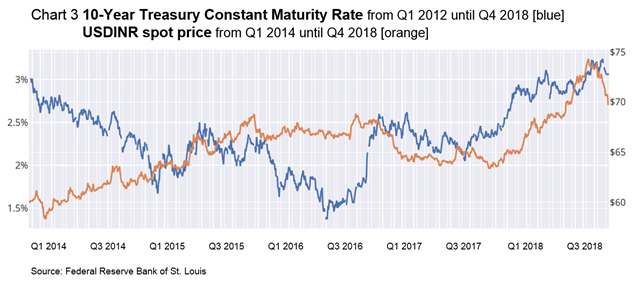

Since 2017 Indian firms hold more than half a trillion in dollar-denominated debt, equal to about a third of the total government debt and a fifth of India’s total GDP. Therefore, India’s demand for US Dollars has risen sharply, consequently weakening INR. A situation worsened by the overall rising USD and increasing interest rates in the United States. Especially Fed policies have led to an acceleration in capital outflow over the last year.

As emerging markets generally rely on foreign inflows to fund fiscal and current account deficits, the Fed’s interest hikes over the last year have boosted the fall of INR. Emerging markets are becoming increasingly uninteresting for overseas investors, who have been pulling their money out of the EM bond market for the better part of 2018. This on the one side reinforced the fall of the Rupee but on the other side led to an increase in bond yields.

The slightly higher yields dampened the fall of the Rupee as investors bought more than USD 400 million of Indian debt. However, there is only limited upside bias for bond yields since the RBI is inflation-focused and is unlikely to use interest rates to stop Rupee’s depreciation, thus India’s 10-Year Government Bond yield has increased by almost 180 bp since mid-2017 and peaked at 8.18% this October, an almost 4-year high, taking prices down. Furthermore, Indian government bond yields as compared to the global bond market only partly convince investors to enter the markets as US yields hit a record high this year with the US 10-Year Treasury yield breaching the 3.2% mark and currently being at around 3.0%.

The effect of oil prices on INR

The rationale behind the Rupee’s dependency on commodities can be split into two drivers – the import and the export of goods – in short, the current account balance. India’s most important commodity exports include oil, refined diamonds as well as rice and metals. As of 2016, the biggest groups of commodities imported by India are oil, precious metals, unrefined diamonds, and metals.

It is the world biggest importer of gold and third biggest importer of oil. Negative effects of price increases in precious metals are largely offset by India’s export volume in this sector. Besides, the effect of weakening gold prices during the second and third quarter this year is offset by the negative correlation between gold and USD.

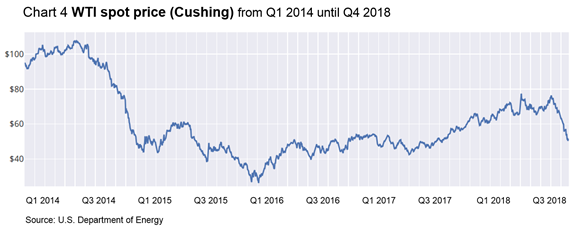

What is more, the oil price development over the past years and especially weeks has had major effects on India’s economy and its currency. Crude oil’s persistent gains have contributed to the continuous decline of INR and widened the current account deficit. As the whole economy is highly dependent on oil, the high oil prices posed a threat to India, because of the inverse relationship to oil prices with a correlation of -0.68.

India is currently importing almost 5 million bbl/d – about two third of its demand – and due to the falling of the Indian Rupee as well as an increment in consumption of crude oil, this number is expected to further rise the following year. It compares to 4.4 million bbl/d in 2017.

After the US imposed sanctions on Iran’s oil industry oil plunged to a 6-month low and broke the $50 mark on November 29. Only days after the announcement INR reversed. India itself is importing heavily from Iran and crude oil imports increased by 36% in October year-on-year. India is the second biggest importer of Iranian oil, as the US has temporarily exempted Turkey, China, India, Italy, Greece, and Japan among others from the ban it imposed on countries purchasing Iranian oil. However, as the 45-day waivers issued on November 14 are going to expire soon, imports will likely shift to Russia, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, and Brazil.

At the moment, an oil price of far below $50 seems unlikely as we expect OPEC to find informal consensus at the G-20 summit this week, leading to an agreement on production policy at the meeting of OPEC and non-OPEC producers on December 6.

As OPEC has already adapted its output regarding the sanctions to make up the shortfall, thereby boosting the overall daily output to the highest since 2016.

In addition, the main drivers of the drop below $50 were a stronger USD and the oversupply generated by the US government selling its strategic reserves.

The outlook for Q1 2019

As of today, we are not expecting a dramatic shift within the Asian-American trade war, neither a further sustained decline of crude oil comparable to 2016.

The increasing dependency on oil and the strong correlations attached to INR make it a highly dependent currency. The RBI seems narrowed down and with inflation and growth at solid levels, there is not much space for additional actions. The quarrels between the RBI and Modi’s cabinet are seen as a rather temporary factor.

The negative development of INR until October 2018 was amplified by geopolitical tensions and increasing volatility in emerging markets.

Even if India were to decrease their current account deficit due to favorable oil prices, the RBI would most likely further depreciate INR in order to stabilize the inflation rate at around its target of 4%.

As we only expect a slightly more dovish Fed throughout 2019, the pressure on the dollar-denominated debt will sustain. In our view, it is likely that Fed will not stop its hiking cycle until the 3.0% neutral interest rate is reached. Together with additional fiscal policies such as the recent rise of import taxes on steel, it is likely that the volatility and speed with which the Rupee will fall is going to decrease. Nevertheless, we expect the Indian Rupee to continue its fall after completing its current correction that is mainly driven by supply-side factors affecting the oil price.

Currently, the USDINR spot rate trades at 69.71. We expect the Rupee to continue its correction at levels around 65.5 to 69 until oil prices stabilize and reverse to higher levels as soon as the Iran waiver expire. Thereafter, we are projecting a further depreciation of INR that will break through the resistance at 74.5 within the upcoming two to three months and to oscillate between 72.5 and 77.5 within the next half year afterward.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours.